How to overcome the planning fallacy when creating marketing plans

How often have you seen your well-considered marketing plan miss its original deadline? Or go over budget?

We’ll wager to guess it’s more often than you’d like to admit. One small consolation: You’re not alone.

Overshooting deadlines and budgets happens so frequently, cognitive researchers have a name for it. It’s called the planning fallacy.

First proposed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979, the planning fallacy is a cognitive bias caused by our inherent belief that we are not likely to anticipate a negative event, which causes us to inaccurately predict how much time, cost, or risk is associated with completing a task regardless of past experiences with similar tasks.

In a 1994 study, 37 psychology students at The University of Waterloo were asked to estimate how long it would take to finish their senior theses. The average estimate was 33.9 days. They also estimated how long it would take “if everything went as well as it possibly could” (averaging 27.4 days) and “if everything went as poorly as it possibly could” (averaging 48.6 days). The average actual completion time was 55.5 days, with only about 30% of the students completing their thesis in the amount of time they predicted. That means that nearly 70% saw their plans for completion go awry.

What are the implications of the planning fallacy for marketers when estimating the time it takes to prepare and manage a plan?

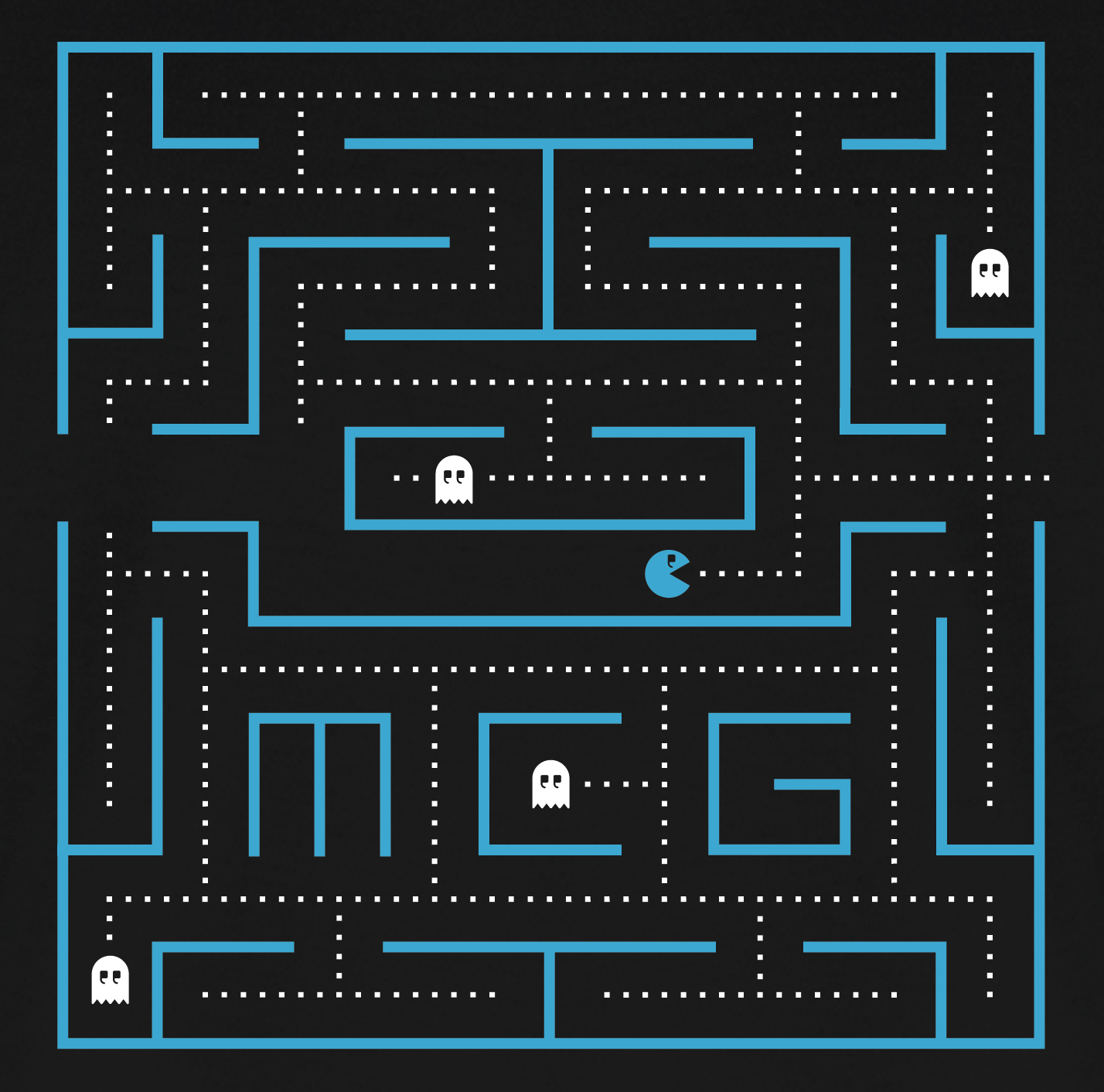

Too often in marketing we idealize how a project will proceed. We don’t like to think about the roadblocks of a project: The extra days necessary for stakeholder feedback, additional rounds of revisions needed to perfect a campaign, new deliverables being added, or our own procrastination. It’s human nature to be inherently optimistic.

There’s even a name for that: It’s called the optimism bias. A recent roundtable discussion on the Freakonomics podcast shed some light on the prevalence of the planning fallacy and its relation to the optimism bias. Roger Buehler, professor of Psychology at Wilfrid Laurier University, confirms that “the planning fallacy is a tendency to underestimate the time it will take to complete a project while knowing that similar projects have typically taken longer in the past.” He goes on to say, “It’s a combination of optimistic prediction about a particular case in the face of more general knowledge that would suggest otherwise.”

Tali Sharot, a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London, has explored the benefits to an optimism bias, explaining that it “drives us forward. It gives us motivation. If you expect positive things, then stress and anxiety is reduced.”

Sharot’s studies have shown that the brain processes positive inputs about the future more readily than negative ones. As humans have evolved, this optimism bias may even guard against hopelessness. Considered in that sense, it’s easy to see how it feeds a planning fallacy.

Yael Grushka-Cockayne, a visiting professor at Harvard Business School, sums it up with a two-word directive to overcome the fallacy: “Look back,” she says. “Look back at all the projects you’ve done, all the projects that are similar to this new project X and look historically at how well those projects performed in terms of their plan versus their actual. See how accurate you were, and then use that shift or use that uplift to adjust your new project that you’re about to start.”

So how do we as marketers prepare for and overcome the planning fallacy?

- Acknowledge that the fallacy exists. None of us are exempt from bad habits and behavioral psychologies. Take measures to accommodate them when planning.

- Plan for failure. Benjamin Franklin once posited, “If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail.” We don’t expect to miss deadlines or budgets, but it happens. Before you start any planning, review past projects of similar scale and scope. How did those turn out? What was their budget compared to the deliverables you have? Were they completed on time?

- Ignore your gut instinct and recognize patterns in past projects. Identify average increases in budgets, timelines or deliverables and apply those to your next marketing plan. While increasing budget or timelines might seem difficult on the front half of a project, doing so will make you look better on the back half, providing you with a win-win situation — either finish on time and budget or, even better, early and under budget.

- Think micro not macro. When considering your marketing deliverables, think through every aspect beyond key milestones. Breaking down a project into smaller sprints increases success rates and allows you to identify more quickly if something is off track.

- Consult with team leads on project budgets and timelines. The more hands are on a project, the more variables and thus opportunity for failure points. Make sure to get team buy-in and validation for project scope before kick-off.

- Record time and budgets for future projects. Whether your organization requires it or not, it’s a good practice to track your time on every project. This serves two benefits: It identifies how your project is trending, allowing you to realign as needed, and more importantly it gives you a record and roadmap for future assignments.

- Optimism can rule the day when we ponder and plan new projects. New marketing projects can be exciting, even fun. It’s important to remember that optimism bias exists, and our unbridled enthusiasm can kick all the roadblocks to the curb, leading us directly to the planning fallacy. The best advice for marketers, then? Build unexpected hurdles or detours into your timeline and budget. Don’t necessarily “plan for the worst,” but keep a running list of things that have led to missed deadlines and blown budgets in the past. Build some of these into your plan. You’ll end up with happier clients and better met expectations.